Although the crimes with which he is charged are very numerous, they have all been cut to the same pattern, and the whole list of them therefore grows rather monotonous. This is not so much because Landru is lacking in criminal imagination as because his first crime was so successful that he had no need to change his methods.

. . . what did he do with the bodies? It is easy enough to reply that he burned them—that is very probable—but what infernal cleverness had he developed in the art of incineration? There is no crematory, no matter how perfect, which can reduce a human body to an impalpable bit of cinder.

. . . Since the time of Troppmann, no such series of crimes has been heard of, and no misdeeds so cruel and methodical have been brought to trial; and yet Landru has become a kind of comic personage. Comic songs are sung about him. He is represented on the stage, and for all I know some impresario has already asked for first rights on a possible American tour if he should in the future be acquitted.

. . . the real puzzle of the Landru case is less the mentality of the criminal than the character of the popular interest taken in his deeds. — Edgar Troimaux and an anonymous Englishman, "Landru: The Comic Side of Murder," THE LIVING AGE (December 17, 1921)

AN ATROCIOUS MURDERER according to the verdict of the French courts became, during his trial, the most hilarious subject of the French Capital.

Popular places of entertainment were filled with sketches, revues, motion pictures all dealing with Landru, whom the London Outlook describes as "a dull, middle-aged, repulsive-looking, bald-headed, Assyrian-bearded man, who is believed to have killed ten women and to have deceived and swindled two hundred and seventy-three."

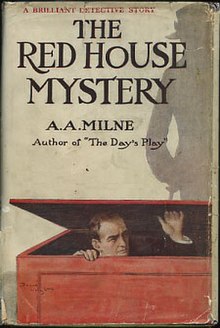

Here is scarcely thought, at least in Anglo-Saxon countries, to be material for jokes; certainly not for universal laughter, and the incongruity leads this English weekly to a serious inquiry into the French state of mind that can make such things possible. . . . — "A British Diagram of French Macabre Humor," THE LITERARY DIGEST (January 14, 1922)Certainly the Landru case had considerable influence, both then and even later; the Wikipedia article section "In popular culture" details just a few Landru references in literature, films, and television, including episodes of Twilight Zone and Star Trek.

Category: True crime

+-+Posed+cast+shot.jpg)