WHENEVER the body of Herman Overcoat, the prominent millionaire, is discovered in the hermetically sealed chamber with a mysterious eggbeater through its œsophagus, or a single shot rings out above the merriment of the English house party and Lady Diana Milkshake turns light mauve as the butler announces with horror in his tones that something strange must 'ave 'appened to the Master, life begins to take on a livelier and brighter tinge for most of us. Even literary critics are perfectly willing to put the latest Siamese masterpiece back in the refrigerator for a while until the mystery of who secreted the star sapphires in the old family retainer has been satisfactorily solved. It was not always thus.

As in the case of the more baneful drugs, the confirmed [detective story] addict can recognize a fellow addict almost at a glance—and when, out of a large and noisy party, two highly incompatible people sit for hours engrossed in quiet talk, oblivious of the revelry, it is quite probable that they are by no means discussing what you think they are but merely swapping conclusions as to whether Mrs. Rinehart's The Red Lamp has quite the same fine frenzy as The Man in Lower Ten or—eternal question—whether Holmes will ever return to Baker Street.

There is not only a body of the reading public which reads detective stories constantly—there is a considerable body which seems to read nothing else.

Literary fads and fashions pass—the detective story is a constant.

That is one of the refreshing things about the detective story—it does not make for conversational bunk. And, as far as detective stories are concerned, that pest of the world, the lackadaisical reader, does not exist.

There were good detective stories before Holmes, there have been good detective stories after him—but it seems only just to say that no single character so completely dominates a subsection of literature. I revere Dupin and admire Lecoq—Nick Carter, Rouletabille, Randolph Mason, Lord Peter Wimsey, Max Carrados, Inspector Furneaux, have their several places in my affection—but Holmes is the master, after all, and the assiduous attempts of various other detective story writers to make their sleuths as unlike Holmes as possible have only succeeded, in general, in making them rather more like him than ever, except in the region of the intelligence. Of course there are exceptions—Father Brown is one—but then almost any character of Mr. Chesterton's should be an exception to practically any rule.

I am merely offering the suggestion that the average reader sometimes has a certain appetite for plot, physical excitement, and definite villainy not entirely satisfied by the best of the modern novels and that, in the detective story, he finds all these things in full measure.

. . . in the average detective story an ingenious complication will carry a deal of crude writing as long as the narrative thread is direct and clear.

Elaborate descriptions of nature, tenuous states of thought, involved psychological processes, love scenes (except of the briefest and most conventional description), are not for him [the average detective story author]. Ingenuity, adroitness, deception, the ability to tell an exciting, straightforward tale—these are his tools.

Father Brown is one of the few modern detectives who never remind one of Holmes, and there is at least one moment in his adventures quite as good as the discovery of the footprints of the hound in The Hound of the Baskervilles.

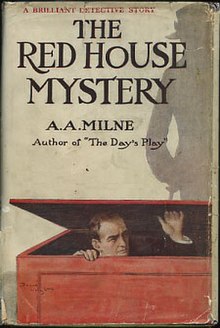

[Milne's The Red House Mystery is] a freak exhibit—strictly speaking, the detective story should not be sullied with humor . . .

The days of uncertainty and dubiety for the [detective story] industry are over—the detective story is as firmly established in our national consciousness as toothpaste, B.V.D.'s, and the Spirit of Rotary.

. . . when all is said and done, murder is the backbone of the detective story. Kidnaping, stolen jewels, arson, piracy, mayhem—they are all very well in their way, but there is something about a good satisfactory murder that makes them seem trifling. For preference an English murder (though again, I am not particular). — Stephen Vincent Benét, "Bigger and Better Murders," THE BOOKMAN (May 1926)Benét notes that there are a few "unnecessary excrescences" in mystery stories, and he concludes his article with "an avowedly personal list of pet abhorrences too often present in [my] favorite literary pablum."

Category: Detective fiction

No comments:

Post a Comment